Project Dogma

Production Journal 01

⇲ Processes and Techniques

When drafting the Phase 1 production plan, I intentionally kept some flexible room, since I could not accurately predict how far I would progress by Week 10. Looking back now, I can see that the actual outcomes differed from my initial expectations in several ways. Some tasks I anticipated would be time-consuming were completed more quickly than expected, while others I thought would be straightforward ended up requiring significantly more time.

Across the ten weeks of production, I spent roughly seven to eight weeks on asset creation, testing, and feasibility verification, which left limited time for story development and almost no time at all for polishing.

During Weeks 1–6, my work focused primarily on creating the character assets, which included modeling, texturing, rigging, grooming, building morph targets, setting up blueprints in Unreal Engine, testing facial motion capture and physics simulations. Most of the work was completed in Blender and Unreal Engine, with some texture painting done in Procreate.

↳ Character modeling, texturing, binding, groom, etc.

↳ USD workflow for environment creation across Blender and UE

↳ initial test of Akashic Tree via Blender geometry nodes

I also worked on building the full room environment, which involved additional modeling and texturing tasks. I also used Hunyuan-3D (Tencent’s AI modeling tool) to speed up the creation of some pieces of furniture in the scene. The environment setup process ended up being partially manual and partially AI-assisted.

Modeling and retopo by AI → Manually fixing issues in Blender

→ Import with USD scene to UE

Through this workflow, I found that handing complex organic models over to Hunyuan-3D could generate usable results quite efficiently. However, for hard-surface assets with layered structures, the AI approach was not necessarily faster than modeling by hand, because fixing the mess of unconnected or incorrectly connected vertices and overlapping faces often required even more time. Overall, my workflow for this part involved assembling the scene in Blender, exporting it as .usdc files, and then using the USD Stage Editor in UE to synchronize updates to the UE level.

In addition to the “static” assets prepared mainly in Blender, I also spent a substantial amount of time in Unreal Engine working on character “animation” assets. Based on their different purposes, I would categorize the assets I created into three types:

1. control rigs for keyframe animation;

2. control rigs and animation blueprints for runtime procedural animation;

3. the setup for facial motion capture.

For the control rigs used in keyframe animation, I primarily followed tutorials from the YouTuber @ProjProd, adapting his approach to allow simultaneous IK/FK manipulation as well as physics simulations.

↳ Control Rig for keyframe anim

The second system was a Full Body IK rig with complementary animation blueprint, which I built because, when I first started learning rigging last year, I happened to see some UE official demonstration of a dragon character with procedural animation fully driven by Control Rig. The rig responded to real-time user input without relying on any pre-made keyframe animations. I found this incredibly impressive, and this project gave me the opportunity to implement a similar approach myself. I referenced various video tutorials and Unreal documentation throughout the process.

The unique point of this technique is that, when the player controls the character, no pre-made keyframe animations are involved. In a traditional pipeline, a character requires many individual animations — walk, run, turn, stop, and so on — combined and switched through state machines in an animation blueprint. In contrast, procedural animation driven directly through Control Rig inside the animation blueprint allows much greater freedom and can respond to far more nuanced user input, since the motion is generated entirely from self-defined math equations: idle movement created from oscillating cosine functions; feet and tail rotations derived from the neck’s relative transform; secondary motion for the hands; velocity processed through a spring interpolation, etc.

At the moment, my setup achieved basic movement animation, parametrically driven in real-time, none key frame animation clip involved. My next step is to incorporate more user input data such as the gamepad accelerometer and gyroscope data to create more varied and interesting real-time procedural motion.

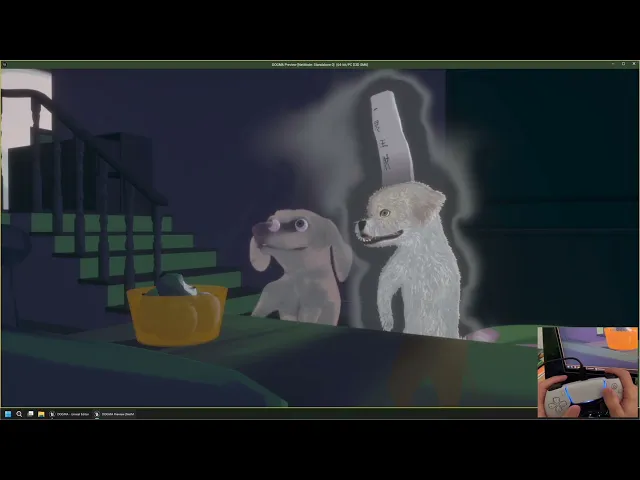

↳ One control, infinite possible floating ghost dog

The final component was the facial motion capture setup. During pre-production, I researched and tested the two methods available in Live Link Face: the new MetaHuman Animator workflow and the ARKit mode. Although the MHA method can potentially produce higher-quality capture results, it requires a much more complex setup and significantly more post-processing for custom characters. After weighing the options, I chose the ARKit mode because it is already a mature workflow with extensive documentation and community posts. It uses the depth sensor on Apple devices (the technology behind Face ID) to capture facial expressions and output the corresponding blendshape values.

For my custom character mesh, I created 24 of the 52 blendshapes defined in Apple’s documentation and successfully connected the entire capture pipeline in UE. The experience was quite amusing, as I was essentially remapping human facial expressions onto a stylized dog character.

↳ Apple’s documentation and the blend shapes for dog

Certain exaggerated mouth shapes that humans can easily produce are impossible for the dog’s long muzzle, while the dog’s expressive nose and tongue movements are things humans cannot replicate. Still, once the setup was completed, seeing the first real-time capture driving the dog’s face was both surprising and very funny.

↳ Facial mocap via Live Link Face ARKit mode

From Weeks 6–8, a significant amount of time was dedicated to look-dev: repeatedly revising and testing shaders, materials, textures, and lighting. This phase felt bittersweet: I found it genuinely engaging, and there were many moments of accomplishment, but it also came with frustration and a sense of powerlessness at times. I tried a wide range of approaches over multiple iterations, and although it was challenging, I learned a great deal. Most of this process took place inside UE, experimenting with blueprints, and occasionally consulting LLMs to quickly learn concepts or generate code, which I would then modify and refine.

By Weeks 9 and 10, I realized that time was running out. No matter how much I wanted to continue refining the shaders, I had to start assembling everything and implementing the level—despite many assets still being far from perfect. Unsurprisingly, combining all the components revealed new issues that only became obvious once everything was put together.

↳ The culprit

⇲ Challenges and Solutions

As the saying goes, “the first step is always the hardest” — though in my case, the middle and the ending were just as difficult. The technical components span many areas, and many of the ideas I wanted to try simply did not have any complete or ready-made solutions available online. Much of the process involved exploration: searching for tutorials and documentation, learning new techniques on the spot, identifying issues, testing alternatives, and iterating repeatedly.

My goal was to achieve a stylized, painterly look, as having a visually distinctive style is very important for an independent game project. I knew I wanted a hand-painted aesthetic, so I studied various color-theory tutorials used in illustration. I referenced an illustrator whose work I really admire for its drama and storytelling qualities, which aligned closely with the style I had in mind. Conveniently, he had a video on Bilibili explaining his color approach, so I attempted to translate those ideas into a master material that would dynamically shift the colour tendencies of the scene while maintaining visual harmony.

↳ Some notes and ideas

My first few attempts placed all color adjustments and the cel-cut logic inside a master material. The idea was to first get the directional light vector, use it with a custom material function to derive a cel-cut gradient mask (the light–shadow color division seen in illustrations), and then apply further operations on top of it. For color manipulation, It would take either an intrinsic color from a parameter or texture samples, convert them to HSV, and then perform adjustments.

Two variables, the Environment Color Hue Degree and Light Color Hue Degree (0–360) were stored in a Material Parameter Collection. Through custom code, the shader interpolated between hues by computing the shortest angular distance on the hue ring and outputting that distance as an alpha factor for later saturation adjustments. The gradient mask derived from lighting information determined the direction of the hue shift. Saturation adjustments followed the same logic, and value calculations combined intrinsic value and the gradient mask.

The light and environment colors were manually defined, typically within a complementary warm–cool range (about 90–120 degrees apart). The light color influenced mostly the lit regions, while the environment color had more impact on the shadows. When light influence was dominant, highlights became more saturated and shadows less so, and vice versa.

However, these early approaches had two major issues:

1. Like many stylized UE materials, it only react to a single lighting direction.

To address this, I experimented with adding fake point lights by manually defining their positions, intensities, and ranges in the Material Parameter Collection. In the shader, it combined these with world-position data to calculate falloff and integrate them into the gradient mask. But this approach became overly convoluted, introduced unnecessary computation, limited the number of light sources, and was highly unfriendly for scene adjustments. In sum, it was not a viable solution.

2. The color adjustments were unsatisfactory.

Even though the logic followed the illustrator’s color theory, the results had noticeable inaccuracies, and the transitions were not smooth—especially when adjusted dynamically. The colors often shifted in strange or inconsistent ways.

After more research and experimentation, my second phase of attempts focused on addressing these issues. I revisited a method I had previously dismissed: a “physically based cel-rendering” workflow explained by YouTuber @Visual Tech Art. For some reasons I did not like the look of his technique when I first encountered and examined it, but this time, after studying it thoroughly, I realized that his logic was fundamentally sound. To manipulate lighting information for a cel-cut effect within UE’s rendering pipeline, it really does need to occur inside a post-process material.

In short, his method takes the HSV value from SceneColor, applies log2 to obtain an “EV value”, rounds it, and then maps it back with 2^x. I adapted this technique to generate the new gradient mask and moved the hue and saturation adjustments into the post-process material as well. I also discovered that the reason I disliked the method earlier was that it amplified certain Lumen global-illumination artifacts in my scene (especially when screen-traced GI was enabled) — including unstable shadows that shifted with camera movement and the flickering noise within. After numerous tests, I decided to disable Lumen entirely, which made the stylized scene much cleaner.

Another major issue was color continuity. Through further research, I learned that HSV is not perceptually uniform, which leads to jumps in perceived brightness and uneven color interpolation. I needed an intermediate color model that was perceptually uniform and used a polar (cylindrical) representation for hue and chroma. This led me to convert colors into the OKLch (OKlab) color space for manipulation.

Yet another challenge emerged: because human color perception is based on the LMS cone responses — and these perceptually uniform color spaces rely on transformations involving the LMS space — the permissible ranges of Lightness and Chroma are not normalized 0-1 across the full hue spectrum like HSV or RGB. In theory, these color spaces are unbounded, but in practice, the perceivable range differs by hue. Some hues allow very large chroma/lightness values; others permit only small ones. For math operations, this is a disaster. Converting the colors into normalized OKHSV (as suggested in Björn Ottosson’s newer blog post) would require significant computation and was not feasible for real-time rendering.

↳ reference paintings (combined) analyzed in point cloud plots with Oklab (left) and LMS (right) color spaces

When I was completely stuck, I returned to analyzing my reference paintings. I sampled their pixels, converted them into various different color spaces, generated point-cloud plots, and looked for patterns. Eventually, I noticed that in LMS space, the colors, to some extent, tended to form an approximately linear distribution. Based on this observation, I shifted my approach: instead of the previous manipulations, several key colors were defined and the shader combined them with the new gradient mask derived from the quantized EV value, generated a color ramp, and interpolated in LMS space.

In addition to this, I incorporated assets from a previous project and created several supplementary post-process materials, such as an anisotropic Kuwahara filter and pencil-outline effects.

Even so, the results were still far from where I wanted them to be. By this point, it was already Week 7, and during the dailies checking, our instructor Jo reminded me that I cannot keep sinking unlimited time into shader development. I realized that this was becoming a bottomless pit, and it was time to temporarily put it aside.

↳ some previous versions of post-process shader

↳ Quantized ‘EV value’ for gradient mask

↳ Hue lerp bug

During Weeks 9–10, while creating the cutscene, I decided to once again make use of Control Rig and introduce an interactive element. During the slow-motion sequence where the dachshund character floats through the air, I wanted the player to control the dog’s two front paws using the gamepad triggers. When I first implemented this idea, the results were terrible — the paws could technically be controlled, but the motion was stiff, jittery, and completely disconnected. The physics effects I expected also seemed to have no impact at all.

After analyzing the issue, trying many different approaches, and searching online, I eventually discovered the root cause: in that section of the animation, I had been using a time dilation track in the Level Sequencer in order to slow down the animation to a 0.2× speed. What I didn’t realize was that this convenient method actually alters the entire world’s time dilation, which affects both user input and the physics simulations running inside the Control Rigs. Once I moved the timing logic out of Sequencer and into the Level Blueprint instead, the problem was resolved.

When my classmates picked up the controller in the final class and started making the dog perform frantic “dog-paddle” motions in mid-air with its front paws, they burst out laughing. Seeing their reaction made me genuinely happy — it turned all the earlier challenges into a sense of accomplishment.

↳ Level Blueprint

↳ numerous tracks in the sequence

↳ hand drawn UI for indication

Aside from all of this, there were also some unexpected challenges caused by Unreal Engine itself.

Another example was even more dramatic. When I was implementing the interactive animation, I needed to trigger Level Blueprint events from Sequencer via a Blueprint Interface. There happened to be a very detailed official Unreal Engine document explaining exactly how to achieve this, with one section specifically highlighting two similar functions — one marked with a green check, and the other with a large red X, warning users not to confuse them. Ironically, it turned out that the function marked with the red X was actually the one that worked, and the “correct” one suggested by the documentation did not work at all. Several community posts and videos also pointed out this inconsistency, confirming the issue.

⇲ Play-Through

⇲ Learnings and Improvements

As a very detail-oriented person, there is a lesson I understand in theory but consistently fail to put into practice: many aspects of production have no upper limit. It is possible to keep polishing one single element forever and become extremely specialized in it, but for an indie game production, that approach can be disastrous. What matters most is building a rough, functional version first and refining it later, rather than hesitating at every step and spending excessive time on details from the beginning.

I do had many ideas that I could not complete within such a short time. For example, regarding music, since September, if I had the chance, I would use the same motif in the assignments for my composition class, since I feel like many game and film soundtracks I enjoy reuse a motif across multiple tracks as a subtle thread that connects the entire work. At this point, I have several pieces that fit the mood of the beginning scene, but the orchestration and arrangement still need substantial refinement. Some of my ideas would also require integrating Wwise, which would take additional time to implement.

↳ Ghost dog theme candidates

⇢Tom's Journal

⇢Dec 2025

⇢swipe or scroll⇢